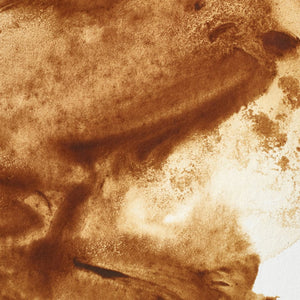

Umber, a dark brown, is part of the prehistoric palette of earth pigments, alongside red ochre, yellow ochre, calcite white and carbon black ochres. These pigments were found in a natural state and mixed with rudimentary binders, then painted – often in the shadows deep inside caves.

It is often thought that raw umber is named after Umbria, the mountainous region in central Italy where it was first extracted in the 15th century. However, another theory is that the name umber bears a connection to this colour’s use in the painting of shadows. Much like the word umbrella, it shares the Latin root for shadows: umbra.

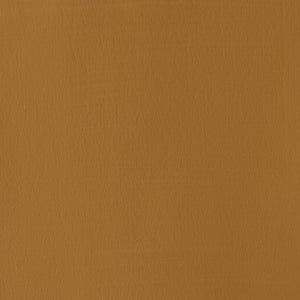

Although Umbria was the first major region where raw umber was sourced commercially, this type of iron oxide and manganese clay soil is found in many parts of the world, and the finest grade of raw umber is said to originate from Cyprus. When found in its natural form it is referred to as raw umber and when heated to high temperatures it becomes burnt umber, which has a darker red hue.

Although the medieval palette included umber, a brighter spectrum of colour combinations, such as azurite (blue), cinnabar (red) and verdigris (green), was favoured. But later in the Renaissance, when artists were painting more naturalistic scenes than the graphic images typical of medieval painting, the earthiness of umbers and siennas were brought back into the fold. The Early Netherlandish master Hieronymus Bosch introduced raw umber in the shadows of his famous triptych ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’ (1490-1500).

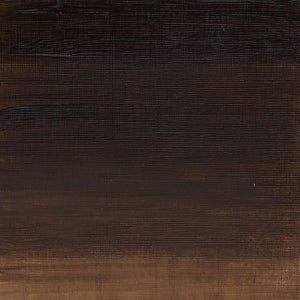

Raw umber’s greatest association with the use of shadows is found in the Baroque chiaroscuro style of painting. Chiaroscuro, Italian for “light-dark”, is a visual technique that champions extreme contrasts in light and darkness to create a dramatic effect, usually with a bright light shining on the figure and a dark background from which the figures emerge. Artists using this technique were Caravaggio (‘Supper at Emmaus’, 1601), Rembrandt (‘Self-portrait as the Apostle Paul’, 1661) and Vermeer (‘The Milkmaid’, 1650).

Raw umber became a more attractive alternative to black in shadows, which we can see in ‘The Milkmaid’, where the semi-transparent brown is applied to the background’s wall to provide a warmer shadow than that achieved using black painting alone.

During the 19th century raw umber’s popularity decreased as the Impressionists developed approaches to the painting of shadows that relied on neither black nor umber. Instead, artists such as Monet adopted elements from the relatively new theory of complimentary colours. Violet, for example, as the complementary of yellow, the colour of sunlight, was used to create shadows. Other shadows and browns were made from mixtures of red, yellow, green and blue in combination with new synthetic pigments such as cobalt blue and emerald green. Even in later years such was the impact of that shift that Salvador Dali discusses his aversion to raw umber in his book ’50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship’ (1948).

But despite these historic fluctuations in the popularity of raw umber, this versatile colour continues to be a go-to in many painters’ palettes for under-painting, monochromatic works, and the rendering of the shadows from which its name derives.

It is often thought that raw umber is named after Umbria, the mountainous region in central Italy where it was first extracted in the 15th century. However, another theory is that the name umber bears a connection to this colour’s use in the painting of shadows. Much like the word umbrella, it shares the Latin root for shadows: umbra.

Although Umbria was the first major region where raw umber was sourced commercially, this type of iron oxide and manganese clay soil is found in many parts of the world, and the finest grade of raw umber is said to originate from Cyprus. When found in its natural form it is referred to as raw umber and when heated to high temperatures it becomes burnt umber, which has a darker red hue.

Although the medieval palette included umber, a brighter spectrum of colour combinations, such as azurite (blue), cinnabar (red) and verdigris (green), was favoured. But later in the Renaissance, when artists were painting more naturalistic scenes than the graphic images typical of medieval painting, the earthiness of umbers and siennas were brought back into the fold. The Early Netherlandish master Hieronymus Bosch introduced raw umber in the shadows of his famous triptych ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’ (1490-1500).

Raw umber’s greatest association with the use of shadows is found in the Baroque chiaroscuro style of painting. Chiaroscuro, Italian for “light-dark”, is a visual technique that champions extreme contrasts in light and darkness to create a dramatic effect, usually with a bright light shining on the figure and a dark background from which the figures emerge. Artists using this technique were Caravaggio (‘Supper at Emmaus’, 1601), Rembrandt (‘Self-portrait as the Apostle Paul’, 1661) and Vermeer (‘The Milkmaid’, 1650).

Raw umber became a more attractive alternative to black in shadows, which we can see in ‘The Milkmaid’, where the semi-transparent brown is applied to the background’s wall to provide a warmer shadow than that achieved using black painting alone.

During the 19th century raw umber’s popularity decreased as the Impressionists developed approaches to the painting of shadows that relied on neither black nor umber. Instead, artists such as Monet adopted elements from the relatively new theory of complimentary colours. Violet, for example, as the complementary of yellow, the colour of sunlight, was used to create shadows. Other shadows and browns were made from mixtures of red, yellow, green and blue in combination with new synthetic pigments such as cobalt blue and emerald green. Even in later years such was the impact of that shift that Salvador Dali discusses his aversion to raw umber in his book ’50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship’ (1948).

But despite these historic fluctuations in the popularity of raw umber, this versatile colour continues to be a go-to in many painters’ palettes for under-painting, monochromatic works, and the rendering of the shadows from which its name derives.

![WN PWC KAREN KLUGLEIN BOTANICAL SET [OPEN 3]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/136448.jpg?crop=center&v=1724423264&width=20)

![WN PWC KAREN KLUGLEIN BOTANICAL SET [FRONT]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/136444.jpg?crop=center&v=1724423264&width=20)

![WN PWC ESSENTIAL SET [CONTENTS 2]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/137579.jpg?crop=center&v=1724423213&width=20)

![WN PWC ESSENTIAL SET [FRONT]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/137583.jpg?crop=center&v=1724423213&width=20)

![W&N GALERIA CARDBOARD SET 10X12ML [B014096] 884955097809 [DIMENSIONS]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/138845.jpg?crop=center&v=1724893209&width=20)

![W&N GALERIA CARDBOARD SET 10X12ML [B014096] 884955097809 [ANGLED]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/138863.jpg?crop=center&v=1724893209&width=20)

![W&N PROMARKER 24PC STUDENT DESIGNER 884955043295 [FRONT]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/78674_d4d78a69-7150-4bf4-a504-3cb5304b0f80.jpg?crop=center&v=1721326116&width=20)

![W&N PROFESSIONAL WATER COLOUR TYRIAN PURPLE [SWATCH]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/136113.jpg?crop=center&v=1724423390&width=20)

![W&N WINTON OIL COLOUR [COMPOSITE] 37ML TITANIUM WHITE 094376711653](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/9238_5073745e-fcfe-4fad-aab4-d631b84e4491.jpg?crop=center&v=1721326117&width=20)

![W&N WINTON OIL COLOUR [SPLODGE] TITANIUM WHITE](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/131754_19b392ee-9bf6-4caf-a2eb-0356ec1c660a.jpg?crop=center&v=1721326118&width=20)