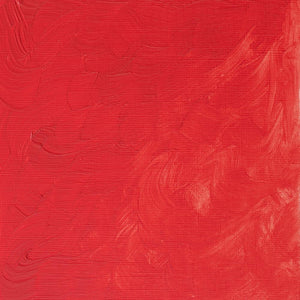

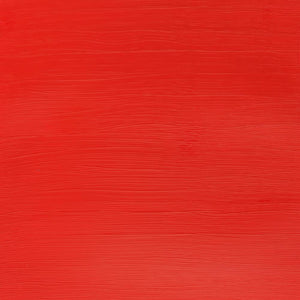

The brilliant and distinctive red of vermilion has been used extensively across thousands of years of art history, from the art and decoration of ancient China and Rome through to the manuscripts of the middle ages and the paintings of the Renaissance.

The origins and hazards of vermilion

Naturally occurring vermilion is an opaque, orangish red pigment and was originally derived from powdered mineral cinnabar, the ore of which contains mercury – making it toxic. In fact in ancient times many of the miners who extracted the ore paid a high price, losing their lives. The word vermilion is derived from the French vermeil, meaning any red dye, which in turn comes from the Latin vermiculum, a red dye made from the insect Kermes vermilio.

China's role in synthesising vermilion

China has been credited with first synthesising vermilion from mercury and sulphur. The earliest known description of this process dates from the 8th century. China red, as it became known, was an everyday part of Chinese life, from palatial red lacquers to the printing pastes for personal name stamps and the red calligraphic ink reserved for emperors.

Vermilion's prestige and value in ancient Rome

Vermilion was equally revered by the Romans who painted the faces of their triumphant generals with it. The vermilion-coated faces were to match the vermilion visage of the image of Jupiter Capitolinus in the temple on the Capitoline Hill. Because pure cinnabar was so rare, vermilion became immensely expensive and the price had to be fixed by the Roman government at 70 sesterces per pound – ten times the price of red ochre.

The evolution and widespread use of synthetic vermilion in Europe

The story of a highly expensive, highly sought after colour continued into the 12th century, when synthetically produced vermilion was used throughout Europe. Costing as much as gilding, it was used mostly to illuminate manuscripts and vermilion still featured in illuminating kits available from the early to mid 19th century.

During the 14th century, the technique for synthesising vermilion became more widespread. Due to the repeatability and control over the process, synthetic vermilion was regarded early on as superior to the vermilion pigment derived from natural cinnabar. The Florentine artist Cennino Cennini, in his book Il libro dell’Arte, had some sound do-it-yourself advice for vermilion customers1:

“Always buy vermilion unbroken, and not pounded or ground. The reason? Because it is generally adulterated, either with red lead or with pounded brick.”

Dutch innovations in vermilion production

From the 17th century, the Dutch method of manufacturing vermilion was used. Mercury and melted sulphur were mashed, resulting in black mercury sulphide which was then heated in a retort, giving off vapour. When the vapour condensed it produced a bright red crystalline form of the mercury sulphide, which was then scraped off and treated with a strong alkali solution to remove the sulphur. The final pigment was produced after washing and grinding the substance underwater.

The Dutch looked back across the centuries, basing their techniques on those adopted in ancient China. The names cinnabar and vermilion were used freely to describe either the natural or synthesised pigment until the 17th century, at which point vermilion became the more common name. By the late 18th century the name cinnabar was generally applied only to the unground natural mineral.

19th century: the purity of Chinese vermilion vs. European alternatives

By the mid 19th century Chinese vermilion was considered the purest form, especially when compared to the European variety of the time. Due to the high cost of cinnabar, European vermilion was often cut with cheaper materials such as brick dust, orpiment, iron oxide, Persian red, iodine scarlet, and red lead. This debasement of the cinnabar would often make the final pigment unstable in artists’ colours.

20th century decline of vermilion and its cultural significance today

The art world’s interest in vermilion declined during the 20th century owing to its cost and toxicity, and cadmium red became a popular replacement which had comparable colour and opacity. Cadmium Red and Cadmium Red Deep are available in the Winsor & Newton Artists’ Oil Colour range.

Today vermilion is still most commonly synthesised by reacting mercury with molten sulphur, and any naturally produced vermilion is most likely to come from cinnabar mined in China.

Culturally it still has immense significance. In India, Hindu women use vermilion known as sindoor along the hair parting line to signify that they are married. Hindu men often wear the vermilion on their forehead during religious ceremonies. Vermilion also has significance in Taoist culture, where it is regarded as the colour of life and eternity.

References:

- Cennini, Cennino D’ Andrea. Il Libro dell’Arte (The Craftsman’s Handbook). Trans. Daniel V. Thompson, Jr. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1933

![WN PWC KAREN KLUGLEIN BOTANICAL SET [FRONT]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/136444.jpg?crop=center&v=1740654068&width=20)

![WN PWC KAREN KLUGLEIN BOTANICAL SET [OPEN 2]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/136447.jpg?crop=center&v=1740654068&width=20)

![WN PWC ESSENTIAL SET [FRONT]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/137583.jpg?crop=center&v=1740762356&width=20)

![WN PWC ESSENTIAL SET [OPEN]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/137581.jpg?crop=center&v=1740762356&width=20)

![W&N GALERIA CARDBOARD SET 10X12ML [B014096] 884955097809 [FOP]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/138855.jpg?crop=center&v=1740761853&width=20)

![W&N GALERIA CARDBOARD SET 10X12ML 884955097809 [OPEN]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/138856.jpg?crop=center&v=1740761853&width=20)

![W&N PROMARKER 24PC STUDENT DESIGNER 884955043295 [FRONT]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/78674_d4d78a69-7150-4bf4-a504-3cb5304b0f80.jpg?crop=center&v=1721326116&width=20)

![W&N PROFESSIONAL WATER COLOUR TYRIAN PURPLE [SWATCH]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/136113.jpg?crop=center&v=1724423390&width=20)

![W&N WINTON OIL COLOUR [COMPOSITE] 37ML TITANIUM WHITE 094376711653](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/9238_5073745e-fcfe-4fad-aab4-d631b84e4491.jpg?crop=center&v=1721326117&width=20)

![W&N WINTON OIL COLOUR [SPLODGE] TITANIUM WHITE](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/131754_19b392ee-9bf6-4caf-a2eb-0356ec1c660a.jpg?crop=center&v=1721326118&width=20)